Sh*t happens

Welcome

back! In this post I aim to provide perspective on the issues relating to

faecal contamination and management.

Before

we begin, it’s important to understand the reasons for faecal contaminated

water across Africa. The basic yet controversial answer would be to blame

citizens and development status. However, a more complex answer would question

the dishonesty of ‘improved water sources and inadequate provisioning of proper

management for faecal waste from the top-down level. Of course, we will be

delving into the complex answer.

‘Improved

water sources’

First

things first, we have to narrow down a definition of improved water sources. The WHO/UNICEF Joint Monitoring Programme (2017) report defined drinking water as ‘by

the nature of their design and construction, have the potential to deliver safe

water’ with three conditions: (1) accessible on premises, (2) water should be

available when needed and (3) be free from contamination. I’ll admit, even

writing the ‘so called’ classification for ‘improved water sources’ is

difficult especially after reading Nayebare's

study (2020) which revealed some shocking horrors. The study

revealed that:

~55% of improved water sources comprising shallow hand dug wells and springs showed gross faecal contamination by E. coli.

~51% of on-site sanitation facilities are unimproved.

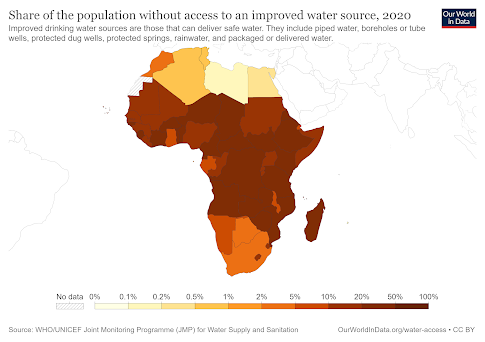

This study investigated water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) conditions in a small town called Lukaya located within Central Uganda, East Africa. It highlights the fragility and vulnerability of on-site WASH facilities which coincides with the inadequacy of current monitoring and maintenance. Whilst other studies find that access to improved sources have improved over time across Sub-Saharan Africa, they have failed to assess the extent to which they have been ‘improved’ therefore ignoring the aspect of ‘safe water’ (Armah et al. 2018). This failure to legitimately improve water sources is reflected in figure 1 which represents a shockingly high share of the population across African countries lacking access to SAFE, ‘improved’ water sources.

Unfortunately it is difficult, as residents across different

African countries are heavily reliant on both improved and unimproved

water sources and so, the dishonest classification of improved water

sources poses serious threats to human health and livelihoods (Mutono et al. 2020). Faecal contaminated water is

highly linked to the transmission of diseases such as cholera, diarrhoea,

dysentery. The rise in diarrhoeal morbidity is determined by poor

hygiene including open defecation, unsafe disposal of faeces and wastewater as

well as poor education and sourcing water from unsafe surface waters (Tumwine et al. 2002). Other related implications

involve difficulties with paying medical costs, being less economically

productive as well as children missing school. These negative social

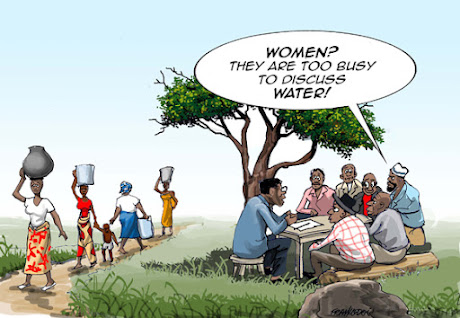

implications of faecal contaminated water ultimately lies in the hands of

top-down authority due to the inadequate and unsafe sanitation systems,

which continues to be a vicious cycle.

I really like how you wrote this as one of the first posts. It is very clear with helpful examples and really does help shape the perspective on issues related to management!

ReplyDelete