Gendered sanitation

Hello everyone! Today I will be exploring gendered water and sanitation as well as highlighting an exemplar case study from Egypt, North Africa.

Femme WASH

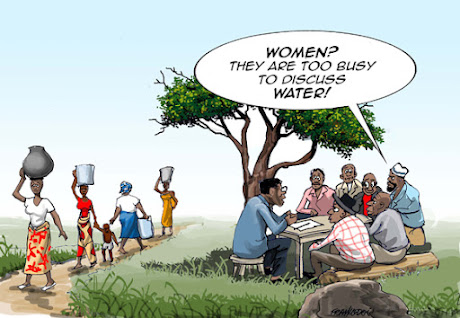

Traditionally, WASH has been gendered as females have an

integral role in engaging with water and sanitation responsibilities, arguably

more than men (MacArthur et al. 2020).

These domestic responsibilities include fetching water, cooking,

cleaning, caring. However, the implications of these gendered experiences

highlight female struggle. The poor WASH conditions make women susceptible to

worsened health including back injuries, stunted development of young girls and

nutrient deficiencies (Pommells et al. 2018). Furthermore, poor WASH is linked to

sexual, psychological, physical and sociocultural violence (Sommer et al. 2014). Unfortunately, these implications occur through inadequate,

far away facilities which increases the risk of sexual violence, fights when

queuing, domestic violence from husbands and menstruation complications (Sommer et al. 2014). Menstruation remains to be an ‘overlooked and poorly

addressed’ issue but this neglect is a result of the male dominated expertise

of water and sanitation engineering and the various cultural norms and taboo’s (Giles-Hansen et al. 2019:

236; Tilley et al. 2013).

Despite, females being instrumental to WASH and bearing the

brunt of implications, they are rarely given the opportunity to participate, see figure 1.

This exclusion is due to cultural taboos and restrictions posed by their male

counterparts and so, this neglect is a key determinant in the failure of

various WASH projects (Tsekleves et al. 2022).

Empower not disempower

In the early 2000s, a village in upper Egypt, Nazlet

Fargallah approached the Better Life Association for Comprehensive Development

(BLACD) who used a gender-integrated approach to improve water connectivity,

install household toilets and educate communities (Hamman, 2006). This project was

successful and saw the provision of 700 households with two taps, a latrine and

increased education on hygiene (Hamman, 2006). Most importantly the

gender-sensitive approach allowed women to overcome existing power structures,

cultural taboos and resistance from male family members. Astonishingly though,

the project successfully integrated women into programme operations, decision

making as well as prioritising the needs of women (Hamman, 2006). Although it has been 10 years, Egypt

has continued to push for gender equality and women’s empowerment through

supporting education, promoting female entrepreneurship, community leadership

and protecting the most vulnerable (USAID, 2022).

Moving forward, we must consider schemes to improve WASH standards but also create resilient and equal communities. Join me in my last post where we touch upon Cop-27 discussions.

Great post, I love the overview to begin with highlighting key issues with Women in WASH (and I think the cartoon is great). The case study is really interesting - I wonder what exactly was involved in the gender sensitive approach - other than involving women in decision making. :)

ReplyDeleteThankyou for reading my post! Glad to see you enjoyed it. The case study was extremely interesting and surprising that a gender sensitive approach was adopted in the early 2000s. Feel free to check out the case study further here, there are also so many other examples from other countries across the world; https://www.un.org/esa/sustdev/sdissues/water/casestudies_bestpractices.pdf

Delete