Yours Truly Disposal

Welcome back to today’s post on Community Led Total

Sanitation (CLTS) schemes focusing on Kenya, East Africa.

Admittedly, in my last post I criticised top-down authority

as being ill-equipped to tend to the needs of local communities. Equally, it is

also important to acknowledge the failure of local people to accelerate the

success of SDG6. It has been argued that local citizens are sometimes unwilling

to invest in household sanitation improvements due to insecure land tenure,

unable to afford the costs as well as built toilets being seen as culturally

inappropriate (Munamati et

al. 2016; Mara et al. 2010) . Therefore, it is important to

explore a community led project that has encouraged local people to actively

improve their WASH conditions.

‘Tales of sh*t’ 💩

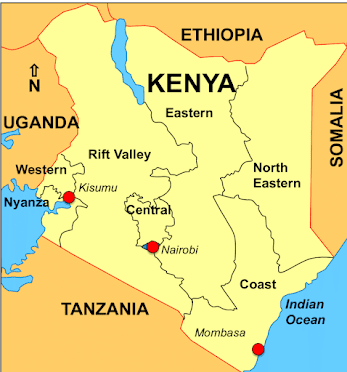

The key for any sanitation project is changing citizen’s mindset to be willing to improve their quality of life and sanitation conditions. The Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) scheme was first introduced in Kenya in 2007 across three districts; ‘Kilifi (Coast Province), Homa Bay (Nyanza Province) and Machakos (Eastern Province)’, see figure 1 (Musyoki, 2010: 151).

The Kilifi district was the first village that was triggered with the initiative. This initiative aims to encourage participatory training, group work and discussions to improve relationships between citizens and those in power (Crocker et al. 2016). However, most strikingly CLTS aims to trigger feelings of ‘disgust, shame and fear’ amongst locals in order to highlight the shocking horrors of open defecation (Musyoki, 2010: 151), shown in figure 2. The training staff work with the community to educate them on how open defecation causes the ingestion of faeces through contaminated water, food contaminated with houseflies, poor handwashing and unsanitary food preparation (Bwire, 2010: 92). CLTS has largely scaled across Kenya and to other countries as they celebrate open defecation free (ODF) status, with communities in South Sudan, East Africa celebrating ODF status just last week (Coombes, 2020).

However…is this scheme truly a bottom up, community led project? The answer is no. This is because the CLTS initiative is mandated by the Ministry of Health as well as having attracted multiple NGO’s and international organisations such as UNICEF. Having said this, these top-down actors support local communities with funding and train citizens so they can become community leaders for the CLTS initiative and take responsibility towards achieving ODF status (Kapatuka, n/d). Perhaps, governments, international institutions and the private sector can learn from the success of this community led scheme whereby communities empower one another to improve their water and sanitation practices.

So now we’ve covered top-down governance,

bottom-up communities, the next post will delve into ecological sanitation 🌍

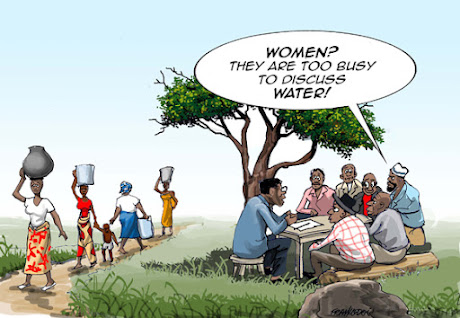

The posts demonstrate a reasonable grasp of water and sanitation issues in Africa, illustrated by the various case studies and engagement with relevant literature. All posts build upon one another with the subtheme of contamination, toilets as a sanitation infrastructure, and sanitation systems of human waste. In a subsequent blog, it will be good to see examples of gendered implications of water and sanitation, as males and females have different experiences of sanitation issues.

ReplyDelete