'Poolitics'

Hello again! Today's piece will be delving into toilets as a sanitation infrastructure provided by top-down authorities.

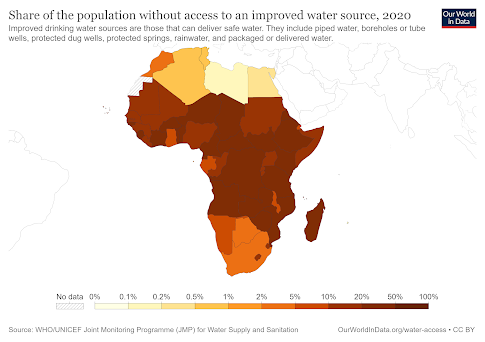

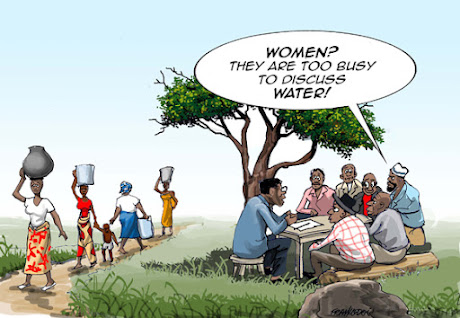

Following on from the last post, I guess the dishonesty discussed comes from the top-down level, well that's an assumption but just as faecal contaminated water is an issue, so are the sanitation systems of human waste. Human excrement is an increasingly politicised process whereby sanitation is at the discretion of government control involving inadequate funding, corruption, unreliable data collection and monitoring (Ekane, 2018). In particular, toilets as a sanitation infrastructure represents these 'poolitics' which carry several social biases and reinforces inequities of colonialism.

'Poolitical protests'

The ‘poo protests’ in Cape Town, South Africa in 2011 highlights the politicised nature of sanitation (McFarlene and Silver, 2016). These protests were concentrated in the Makhaza neighbourhood of the Khayelitsha township to demand access to basic sanitation in this region as well as other informal settlements, see figure 1.

This was fuelled by the 2009 installation of several open toilets by Cape Town authorities with expectations of citizens building their own enclosures. However, 51 residents could not afford this and demanded the city government to pay the bill. As a compromise, the city government-built timber and iron corrugated enclosures rather than building with brick and mortar (Redfield and Robins, 2016). On the grounds of this ‘substandard and racist’ compromise, the ANC’s Youth League destroyed 51 toilets (Penner, 2010). From this movement, the rise of ‘poolitics’ has spread over the African continent, from smashing open, portable toilets in Kosovo (Anders and Zenka, 2014), a Cape Town informal settlement, dumping human waste in public spaces as well as marches on annual World Toilet Day, shown in figure 2. These protests aimed to capture the attention of municipalities to bring to light the lack of adequate sanitary infrastructure, the unsanitary communal toilets and human waste collection.

Criticising power

However,

more importantly the inadequate provision of safe and accessible sanitation

systems brings to light questions of colonialism and discrimination. Sanitation

and politics have always been linked. Dating back to colonial Africa and

apartheid South Africa, sanitation policy would be used to displace the

poorest in society to urban margins away from the affluent, and

middle-class areas (Robins,

2014). In regard to the protests, the

provision of unsafe open toilets represents this failure of a ‘post-apartheid

democracy’ to change the racism, inequality and poverty that is persistent

within water and sanitation systems across Africa (Anders

and Zenker, 2014). The top-down structure of

sanitation provision is therefore criticised as discriminatory and being linked

to ruling past history which continues to lead to the failure of these

authorities across Africa, not to mention the corruption and lack of financing.

In general, the hap-hazard and inadequate provision of toilet infrastructure

brings important questions as to whether those in power are ill-equipped to

tend to the needs of the local level.

Stay tuned for the next post which will explore the argument for bottom up led water and sanitation provision and management.

Comments

Post a Comment